How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.

Annie Dillard

Like most educational administrators/leaders, I have a good deal of discretion in my schedule. There are days, of course, when I have meetings floor to ceiling, but nearly every day I can make choices about how I spent my time. This was also the case when I was a school librarian.

So my work has always been divided between adminitrivia (OKing, time sheets, signing off on purchase orders, etc) and the implementation of larger projects intended to make our schools more effective for more kids.

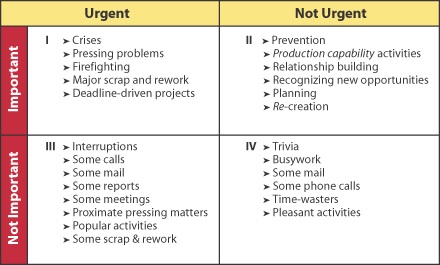

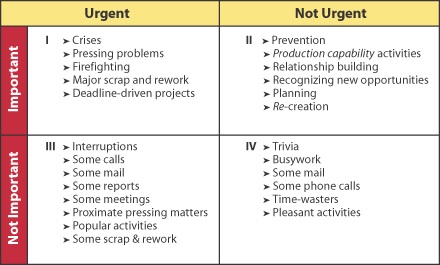

I've long seen Covey's time management quadrant above as a simple but effective means of evaluating one's tasks. He makes, as I remember, some interesting observations about the relationship of the tasks in the different quadrants. The only way to reduce the amount of time spend in Quadrant I is by doing more Quandrant II work. The only way to free up more time to spend on Quadrant II work is to spend less time in Quandrants III and IV. Easier said than done.

Time management (through the lens of Covey's Quandrants) is the critical skill that separates the effective and non-effective school librarian. In an old column (How we spend our days, November 1996), I added some time management advice:

1) Should someone else be doing this task?

As a taxpayer, I hate seeing a professional educator get paid a professional salary to install software, fix a printer, checkout books or babysit with videotapes. When no one else is available to do an essential clerical, technical or paraprofessional task, the professional often winds up doing it. If the professional spends too high a percent of her day on these tasks, guess what? The position gets “right-sized.”

I would rather manage two media centers or technology programs each with a good support staff than try to manage a single program alone. Consider it.

2) Am I operating out of tradition rather than necessity?

Yearly inventories. Weekly overdue notices. Shelf lists. Seasonal bulletin boards. Daily equipment check out. State reports. Skip doing a task for an entire year and see if anyone really notices. When you’re asked for numbers, estimate. A job not worth doing is not worth doing well.

3) Is this a task which calls for unique professional abilities?

John Lubbock once wrote: “There are three great questions which in life we have to ask over and over again to answer: Is it right or wrong? Is it true or false? Is it beautiful or ugly? Our education ought to help us to answer these questions.”

Computers are wonderful devices, but even the most powerful can’t even start to help us answer these questions. A computer can’t evaluate good materials, comfort a child, inspire a learner, write an imaginative lesson, or try a new way of doing things. If you can be replaced by a computer, you should be. I hope every task you do each day - from helping a child find a good book to planning a district wide technology inservice - taps your creativity and wisdom.

Teachers and principals are wonderful people, but you should spend your time doing what they don’t have the training, temperament or skills to do. What is it that you understand about information use that makes you a valuable resource? What productivity software do you know better than anyone else in the school? What communication, leadership or organizational skills do you bring to a project that really get things moving? Ask yourself what it is that only you can do or that you can do better that anyone else in your organization and spend as much of your day doing it as possible.

4) Is this a job that will have a long-term effect?

In a management class I teach, an interesting discussion revolves around whether a professional should help an unscheduled group of students find research materials, even if it means skipping an important social studies curriculum meeting. It is in our nature to help those who seek our help, and that’s exactly as it should be. But too often, the minutia of the job pin us down, like Gulliver trapped by the Lilliputians, and we make small progress toward major accomplishments. Remind yourself that that the big projects you work on often have more impact on your students and staff than the little attentions paid to them. Spend at least one part of everyday on the big stuff.

I'd like to think that this advice still works today. And I like to think even more that I follow it myself.

Image source

Tuesday, August 15, 2017 at 05:08AM

Tuesday, August 15, 2017 at 05:08AM