BFTP: Strictures and creativity: the 5 paragraph essay

Thursday, June 18, 2020 at 07:56AM

Thursday, June 18, 2020 at 07:56AM

Strictures and creativity: the five-paragraph essay

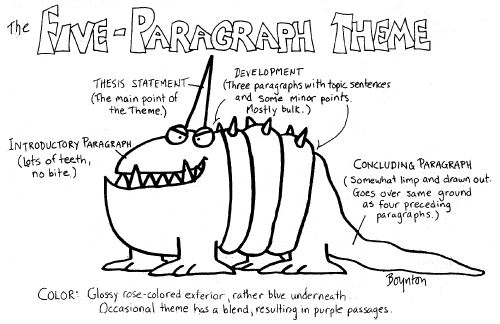

The five-paragraph essay is a form of essay having five paragraphs:

- one introductory paragraph,

- three body paragraphs with support and development, and

- one concluding paragraph. Wikipedia

I learned to write and taught writing myself using the five-paragraph essay as a means of structuring writing. I can't say that I use the form specifically any longer, preferring a more narrative voice, but I am I glad I was taught the form and required to use it. Despite reading that its day has passed, that teachers are stifling creativity by asking students for supporting evidence, a thesis statement, transitional phrases, and a conclusion, knowing the rules of the five-paragraph expository essay is beneficial for all writers.

Good writing is well-organized writing. By asking one's writing students to outline their thoughts, the form helps the reader navigate the topic as well. The old admonition "Tell'm what you're going to tell'm, tell'm, and tell'm what you just told'm helps to effectively structure one's ideas. Stream of conscious writing may work for avant guarde literary types, but an organized essay is a good foundation on which to build solid writing skills.

Organization does not make a compelling piece of writing without credible supporting evidence. By asking for three supporting ideas, reasons, or pieces of evidence, the five-paragraph essay form moves the writing from pure opinion to opinion that has some thought behind it. While not popular among many contemporary politicians, readers like knowing the "why" a stand is taken. Asking students to demonstrate through evidence why they might make a statement is one of the more important whole-life skills one can use - one more human beings ought to practice.

But don't strict rules of organization and evidence restrict creativity as critics suggest? Yes, when creativity is not an expectation. Other strict literary forms - the Elizabethan sonnet, the haiku, even the limerick - have not kept poets from writing original and impactful works. The PechaKucha, a presentation format that allows only 20 images to be shown each for 20 seconds, forces speakers to think qualitatively rather than quantitatively about their message. While teachers need to be careful not to over prescribe requirements of any assignment (As Chris Lehmann warns, "If you assign a project and get back 30 of the exact same thing, that's not a project, that's a recipe."), being creative within the confines of a classic writing structure, can be challenging, but is certainly possible.

The usefulness of the five-paragraph essay is not diminished by word processing, social media, or texting. Structure, organization, and creativity shaped by rules are all attributes of good writing that the form demands, when a good writing teacher demands it as well. Call me a traditionalist, even a sentimentalist, but along with attention to grammar, spelling, and other hallmarks of good writing, I hope teachers keep using this essay format as a tool. Consider how well it served this blog post.