Library ethics for non-librarians - Statement VIII (and final)

Saturday, June 25, 2016 at 05:50PM

Saturday, June 25, 2016 at 05:50PM ALA Library Code of Ethics Statement VIII: We strive for excellence in the profession by maintaining and enhancing our own knowledge and skills, by encouraging the professional development of co-workers, and by fostering the aspirations of potential members of the profession.

While we do need to practice and help others practice the standards of ethical behaviors I-VII, statement VIII, for those of us in education, supercedes them all. Our primary ethical responsibility is promoting meaningful change in our institutions.

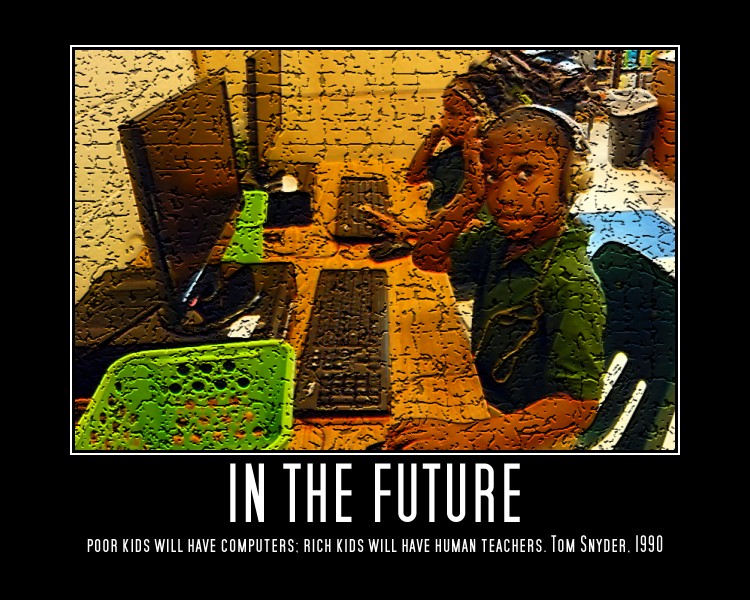

Technology is being used as a catalyst for change in education in the best and worst senses of the word. It has opened avenues toward previously undreamt of information and communication opportunities. It is spurring some teachers to be more creative, more constructivist-based, and more individualized in their instruction. But the chance of technology being used badly is also great as critics like The Alliance for Childhood, Jane Healy, Larry Cuban and Clifford Stoll suggest. Technology can depersonalize education, divert funds from more effective educational practices, and over-emphasize low-level skill attainment as the ultimate educational goal.

As librarians we understand perhaps better than many in education that teaching is a moral pursuit. It is changing the world in a positive way through changing lives of our students in positive way. Technology we must recognize as simply a tool that will help us achieve those changes.

Too many of our schools lack effective leadership for the positive changes that technology can foster or accelerate. In such situations, a clear vision of what technology can and should be doing, well-articulated by the librarian, can have a tremendous impact. We can and should help fill such a directional void. Librarians make especially effective change agents because:

- our programs affect the whole school climate

- we advocate information skills and personalized learning for every child

- we advocate for technology being used to promote problem-solving and higher level thinking

- we have no subject area biases or territories to protect

- we’re extremely charming

While often uncomfortable, the librarian must challenge the system to be an effective agent for change. We do so by working on school governing committees, leading staff development activities, and exemplifying great teaching practices and technology use ourselves. We are involved in curriculum revision and fight for the effective integration of technology and information literacy skills. We write for district newsletters and talk to parent and community organizations. We hold offices in unions and other professional organizations. We write to legislators and attend political functions and school board meetings. We form strong networks with like-minded reformers inside and outside our profession. And throughout these efforts, we keep firmly in mind that technology’s purpose is to empower our students.

Our role as the “teacher of teachers” has never been greater as was alluded to in Statement V. We need to lead formal staff development activities, work on long-term staff development plans and serve as mentors and peer-coaches in our schools. The librarian is especially effective in working with teachers on the meaningful integration of technology into the curriculum through instructional units that include information literacy skills and stress higher level thinking and by designing authentic assessments of performance-based units of instruction. We are the team players, the hand-holders, the encouragers, the cheerleaders, the resource-providers and the shoulders on which to cry. We help improve our institutions by helping to improve the performance of the people who work within them.

As the tools of our profession change with technology and our mission grows to encompass teacher-training and leadership, our ethical duty to upgrade our own professional skills takes on ever increasing importance. My formal education ended with a master’s degree in 1979 from an excellent ALA accredited program. This was before personal computers of any usefulness; before popular use of OPACs; before online databases; before the acceptance of the Internet by the bourgeoisie; before multimedia encyclopedias; before the printing press (well, not quite).

It follows that our ethical duty also includes membership and participation in professional associations devoted to ongoing professional development and attend the conferences and workshops they offer. We must continue to read professional journals and books. We must take advantage of listservs and other forms of electronic communication that help us maintain virtual conversations about our practice.

As Statement VIII concludes, we must foster “the aspirations of potential members of the profession.” A person recently commented to me that one must be mad to go into school librarianship. He’s right, of course, on a number of levels. You have to mad (passionate) for stories, computers, and especially working with kids. You have to be mad (angry) about how poorly our schools underserve too many vulnerable children. And finally, you have to be mad (crazy) enough to believe that you as one individual have the power to change your institution, your political systems, and especially, the lives of your students and teachers. It is a rightful part of our ethical code that we must recruit other madmen and madwomen to our profession.

We should all be on, as the Blues Brothers describe it, “a mission from God” everyday to make sure technology use in our schools is actually improving the lives of our students and staff. Heaven knows that nobody goes into the profession to make money. As educators, our satisfaction comes from actually believing we are doing something that will make the world a more humane place in which to live. The ultimate ethic of our practice is improving the lives of the children who attend out schools. The addition of technology to our schools does not change this; in fact, it may just make it more imperative. Minnesota writer, Frederick Manfred in his poem “What about you, boy?” says it far better than I ever could:

…Open up and let go.

Even if it’s only blowing. But blast.

And I say this loving my God.

Because we are all he has at last.

So what about it, boy?

Is your work going well?

Are you still lighting lamps

Against darkness and hell?