To make it Google-proof, make it personal

Saturday, July 6, 2013 at 06:19PM

Saturday, July 6, 2013 at 06:19PM The principal sin of plagiarism is not ethical, but cognitive.

Brad Hokanson, U of Minnesota

The program for this year's ISTE had a few sessions with "Google-proofing" in the title. Since, I suppose no one copies directly from print sources anymore, "Googling" and "plagiarizing" are synonymous. And as professor Hokanson suggests in the quote above, when there is a direct transfer of information from source to student product - with no cognitive processing stop in-between - little learning occurs as a result of the assignment. It is busy work that no one likes.

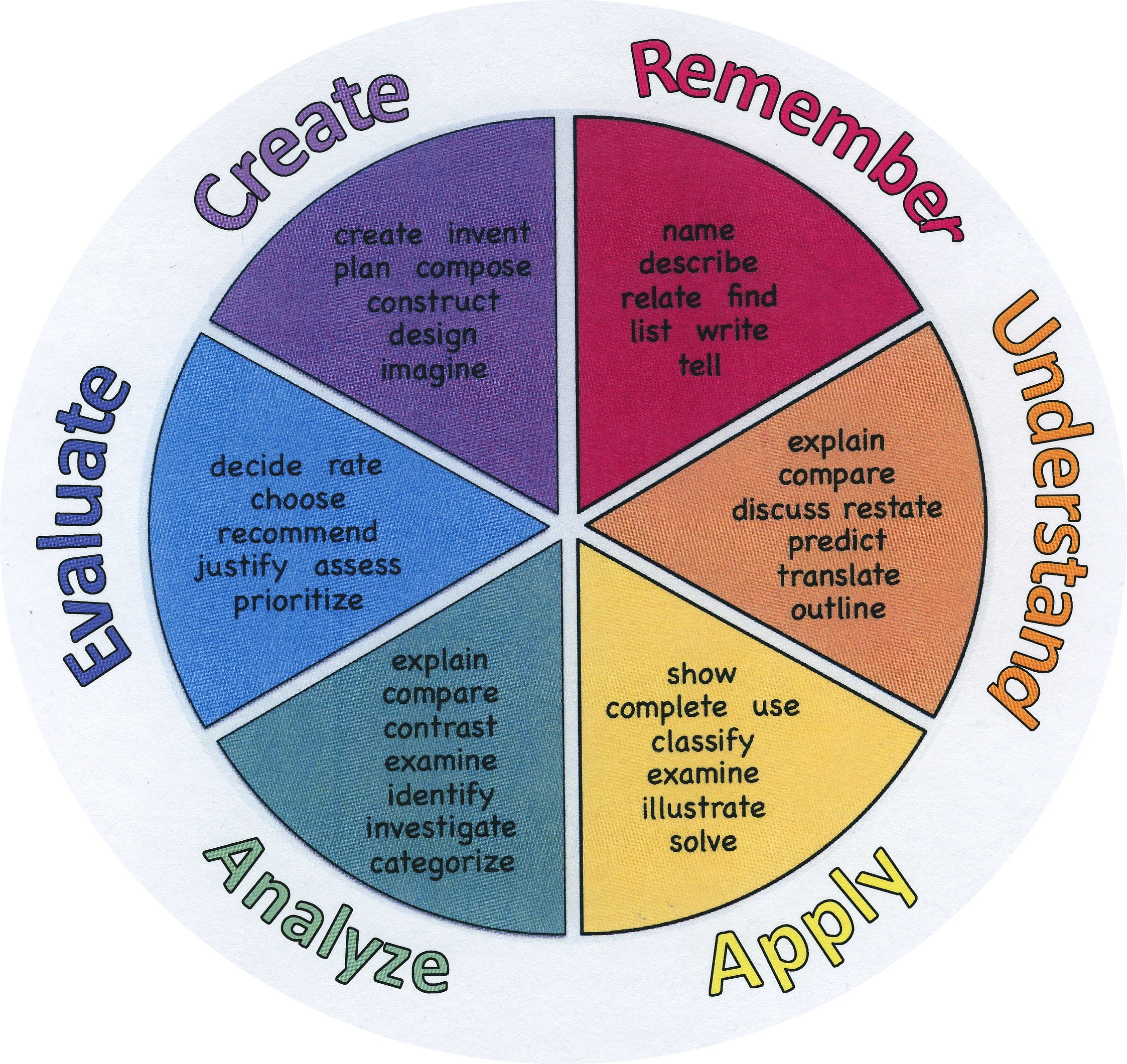

Reducing the probability of plagiarism has been an interest of mine for some time. (See Copy, Paste, Plagiarize, 1997, The Other Side of Plagiarism, 2004, and Plagiarism-Proofing Assignments, 2004). And I have long argued that developing better research and test questions, rather than using Turnitin or other "gotcha" types of technologies, is the best long-term solution to plagiarism. And at the heart of most "better" assignments and assessments is attention to higher-order thinking skills that require original thinking rather than simple recall or reporting of content. The graphic below, one of many, many similar graphs and charts, matches Bloom's Taxonomy to verbs that help create better assignments:

But I don't think just attending to HOTS is sufficient. Assignments and assessments need to be personal as well. Engagement, creativity, and meaning result when the outcome of a project are in some way related to oneself and to those people, places and things one cares about. But what makes an assignment personal? I would suggest four primary means:

1. Allow (or require) the student to relate the academic topic to an area of personal interest. If the assignment is to do research on WWII and the student has a personal interest in horses, have the research question be "How were horses used in WWII battles?"

2. Allow (or require) the student to do inquiry that has implications for him/herself or his/her family. Rather than research a topic about an assigned health issue, ask the student to select a health problem that may be experienced in his/her own family or by someone he or she is close to.

3. Allow (or require) the student to give local focus to the research. Rather than simply studying bats, for example, ask that the student focuses on bats that are local and determine the ecological impact of the region.

4. Allow (or require) that the student's final product relate to a current, real-world problem. If the topic is genetics, ask that the result of the paper be a recommendation of how advances in genetic modification might solve a real problem in the news - hunger, disease, over-population, etc.

None of this is exactly rocket-surgery, but it is a fundamental way of re-thinking the purpose of research (to find real solutions to real problems or to explore topics that are meaningful to the researcher) as well as a natural means of reducing the chance of plagiarism.

Your suggestions for Google-proofing an assignment?

Reader Comments (10)

This is great and goes right along with the "I-Search" type of assignment we were encouraged to try when I got my library/information degree. We weren't even given an assignment other than to try to find something of personal interest we could research for ourselves and how we wanted to present it.

I agree with all your thinking here, but I run into a difficulty with using this method with very young students, who are just learning research skills (say, 1st and 2nd graders.) They need to learn how to do research before they can apply their research. With 3rd graders and up, I have found it useful to tell them why we are doing an assignment - it's not so your teacher can learn about snakes, it's so you can learn how to find information in X kind of source and write that information in your own words, for instance. I think even big kids think they've hit upon a great mystery their teachers don't know about: it's easier to use someone else's work! You can just copy that out and then there's time to play! And anyway, the writer of that site knows more and sounds better than you do! Clear objectives help when student objectives are about doing research rather than drawing their own conclusions, and then you can build on those skills with a more Gproof Encyclopdiaproof assignment follow up.

I think if you make the "and what do you think about it/draw conclusions" leap too soon, students and teachers may end up frustrated at the amount of time necessary on the researching end to really get quality conclusions. And many if us, especially the less aged, are apt to think we know it all already and can write a good position paper with no references, for instance.

So how do others get those early easily googlable but still necessary skills taught so students know how to start?

Hello!

I love the suggestions you give for projects, and thought this blog post belonged under a tab in my LiveBinder for Genius Hour: http://www.livebinders.com/play/play/829279?tabid=4405f55b-4014-cc52-338e-ee3f7e7e536b I think it would be a great post for those who don't know where to start with student choice or catering to student passions. Thanks so much for the effort you put into this post!

~Joy Kirr (@JoyKirr)

Hi Ninja,

The iSearch, the concept I attribute to Ken Macrorie, has been a big influence on this old English teacher. He got it years ago.

Doug

Hi Kate,

I guess it is a bit of a Catch-22 - why are we asking young kids to do "research" if it can't be applied to their learning? For academic sake only? I worry that will turn them off. I hope most inquiry projects can be related to oneself or one's family. If we are researching snakes, can we ask if the snake would make a good family pet or be able to live in one's yard?

Doug

Thanks, Joy. I am flattered to be added to your LiveBinders tabs!

Doug

Thanks for your thoughts, Doug. I actually think it's pretty limiting to have kids research only things related to them and their family. Things that personally interest them, as you mention in point one, will resolve that, but it will require some good instruction on the front end to interest them in broader content - so projects need to follow a content unit, letting kids stretch their interests beyond what they already know. And as a public librarian, I saw a lot of good googleproof projects backfire on teachers who assumed students already had basic research skills and knew the learning outcomes. For instance, the annual "make a list of household products made with petroleum" that sent scores of students to the PL looking for the LIST rather than learning about petroleum and coming up with their own list. Students flat out refused to believe their teacher did not intend them to copy out a list from a book. "Create a family tree for yourself as a medieval character" had similar outcomes. And even when I was in library school, I had a professor who skipped the basics of metadata, catalog records, and library punctuation to sail on into cataloging theory, which left a class full of grad students confused for a semester when a good hour of "this is how it works, here's why it's that way from a historical perspective" and a few basic readings would have set us up for the graduate level work the prof wanted the class to do about theory. Having content knowledge (like basic research skills in the form of a simple assignment) sets students up for great googleproof thinking, but missing content knowledge and missing the point of the instruction slows the learning and leaves students and teachers frustrated. But I'm a big believer in learning process through content learning rather than vice versa. I do think much of this is tied to concrete vs abstract thinking, as well, and so it will vary based on student ages.

It's also to important to help students cite their sources. There are so many new "sources" nowadays (websites, Youtube clips, Tweets, .pdfs, emails), it's even daunting for me to learn how to cite them.

I recently finished a 5,000 word paper and I had to teach myself how to cite these new "sources". There are tools available within Google to cite things within the web, any .pdf I download, or any journal that I download (all with permission, of course!). I had to learn how to use them. Before that, I had to know they existed. I also learned about Endnote software that helps students keep track of their sources and puts them into bibliographic format for a final bibliography. It comes as a stand-alone software (integrated with Word software) but costs money. I used the free web tool for EndNote: End Note Web/a> The free version met my needs adequately.

If students know how to cite sources, they won't feel as great the need to plagiarize. As long as they are citing what they are presenting, it isn't wrong to "copy and paste". I'm talking about the student who is serious about his/her assignment. For the ones that are not serious, they'll find ways to plagiarize even a "personal" piece of work. (Handing in an assignment twice, even if you've done it yourself is considered "plagiarism". In other words, handing in the same assignment for two different courses etc.)

Giving assignments that are meaningful in context and personalized would motivate more students to be serious about the assignment, though.

Before students can become fluent in these tools, the teachers need to be. That's the challenge in the matter and it's the same challenge for a lot of other technology "tools" the kids are supposed to using: coding, Minecraft,... the list goes on!

That is taking strides in the right direction. Plagiarism is now treated as a measure of disobedience by the teacher rather than something that prevents true learning and reasoning to happen for the student. This change in focus from the student to the teacher, is preventing them from exploring alternative methods for helping students develop their cognitive abilities while doing assignments. Like you mentioned, personalizing the assignment is a great way to bring the focus back to the student, and induce true learning to take place. Great post, Doug.

I felt like I should clarify that kids can learn software and become fluent on their own if they are motivated. My own kids are a prime-example of that with Minecraft. (I don't know why I put "Minecraft" in my prior reply.) My point is that if a teacher is going to get their students fluent in using citation software & tools, the teacher needs to know about them first and to be fluent in their use. Otherwise, I can't see those skills being developed in students. What student, on his own, is going to be motivated to learn citation and citation software skills? I wasn't motivated (short of my fear of failing the course) and I was an adult. I found it incredibly overwhelming, in fact. Good thing I had a tutor that pointed me in the right direction.

Vivian,

When it comes to citation, I've always thought we can't see the forest because of the trees. The primary purpose of citation is so that the reader can find the original source for additional information (and, of course, to attribute the ideas to another). Instead of keeping this the primary focus, we get all hung up on the particulars of certain styles (Is it a comma or period after the author's name?), making it a purely academic exercise designed to weed out those unwilling to conform.

Doug

Instead of keeping this the primary focus,

I have always thought we can see the forest because of the trees.

good things great post.