The One-Right-Answer-Mentality (Part One)

Tuesday, March 4, 2014 at 04:39AM

Tuesday, March 4, 2014 at 04:39AM

It is quite strange how little effect school—even high school—seems to have had on the lives of creative people. Often one senses that, if anything, school threatened to extinguish the interest and curiosity that the child had discovered outside its walls. - Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

As a former librarian, I have never lost my desire to read aloud to an audience. While I have finally stopped using hand puppets (at least with adult groups), I still sneak a picture book into my workshops now and again. And one of my favorites in Miriam Cohen’s picture book First Grade Takes a Test (Cohen, 2006).

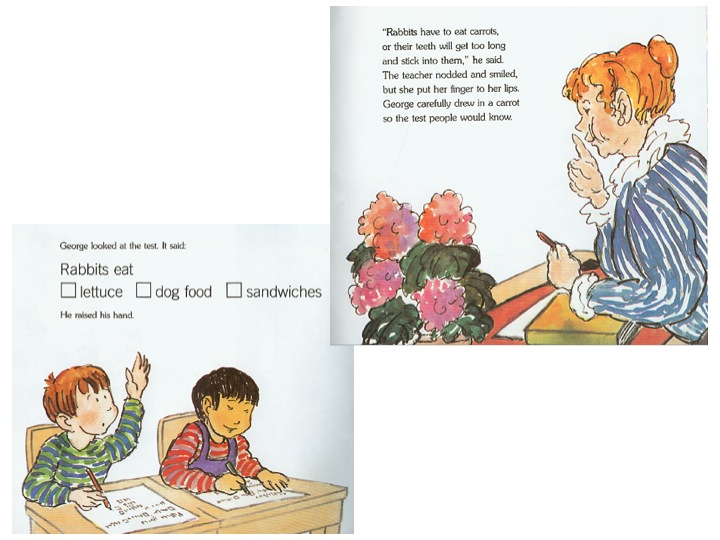

The book describes the frustrations and problem that arise when Danny’s class is given a test to determine who is might qualify for a gifted and talented program. During the paper and pencil normed test, he and his classmates find difficulty in answering questions like:

What do rabbits eat?

What do firemen do?

Which person in a drawing is taller?

Some students, based on their personal experiences, are stumped by the fact that their own “right answers” do not appear as choices. Despite even a student thoughtfully drawing in the correct answer to one question, the test selects a single student, Anna Maria, to be included in the pull-out program.

Ironically, the remaining children creatively resolve an argument over who received a larger cookie by weighing rather than measuring the cookies. And the teacher reminds the class:

The test doesn’t tell all the things you can do! You can build things! You can read books! You can make pictures! You have good ideas! And another thing. The test doesn’t tell you if you are a kind person who helps your friend. Those are important things.

If there is a simpler or more elegant criticism of standardized testing, I haven’t found it. Schooling the United States would be a happier and more effective place were all the employees of the Department of Education required to read Cohen’s little book. And discuss it. Maybe create a poster.

Combatting the one-right-answer mentality

Using testing as a primary (or only) means of assessing student ability has strangled the development of creativity in too many of our children. As we discussed in an earlier blog post, content knowledge and skills (craftsmanship) is a critical component of innovative ideas that have value. No doubt about it. But how do we balance this need for factual knowledge and basic skills with the demands of promoting divergent thinking?

First we need to acknowledge as educators that formative assessments are better learning tools than summative assessments, especially standardized tests.

Extrinsic motivation and a fear of taking risks

In his book Punished by Rewards, Alfie Kohn outlines the deleterious impact than extrinsic motivation - including test scores - has on learning. Through examples and research, he demonstrates five reasons rewards fail: rewards can punish those who do not receive them; rewards can rupture relationships between students and between students and teachers; rewards ignore the reasons for a desired behavior; rewards can discourage risk-taking, and rewards can actually discourage desired behaviors.

Wait a minute. Back up. Didn’t we also discuss that “risk-taking” is one of the hallmarks of a creative person?

Poor first-grader George in Cohen’s book, when confronted with the question of what rabbits eat on the standardized test, carefully drew a carrot on the test form since he knew from personal experience that a rabbit’s teeth needed to be constantly worn down by eating such foods. Not only did George get no credit from his original response, but he may believe the next time that such thinking not only earns him no reward (a good test grade), but punishes him for challenging the authority of the test itself.

Such aversion to risk-taking is common among all students, but especially among those that take pride in their scholastic accomplishments - those A students who have high academic goals and feel they need the straight As and high SAT scores to get into their choice of college (and remain members of good standing in a family who places high value on such measurements).

How likely is a child to write creatively when he knows his teacher gives top grades for formal writing? How likely is a student to suggest an innovative approach to research problem when the number of sources counts more than questioning those sources? Will a high school student take an elective art class knowing that she is sure to ace an academic class that requires little more than regurgitating textbook and lecture notes on the final but may get a lower grade in other electives that may take a more subjective approach to assessment?

This is not a small problem. This is a deep deficiency in how we determine student learning and abilities.

Image source Miriam Cohen's First Grade Takes a Test. Note current edition has a different illustrator.

Reader Comments (3)

Clif's Notes scholars who think knowing rabbits are herbivores is to know everything about rabbits arr terrible managers of business government and charities...too much bad head work is coming out of education system. Please do better work.....

Hi Doug,

Your blog entry reminds of an article, I believe in the New York Times, about the challenges of gifted musicians. If I remember it correctly, these people excel as children and young adults because of their technical ability. The time comes however when if they seek a professional career, especially as a soloist, they must find their own "voice" and style. The transition from the technical to the creative is often quite difficult, for the very reasons you highlight here and in your current series on creativity.

Thanks for your focus on this area.

John

Thanks for this, John.

As I research and write about this topic, I'm discovering that balance is essential between disciplinary rules and creativity. Not sure I have it figured out myself!

Doug